Some infections in pigs can induce reproductive insufficiency, including embryonic loss, mummifications, stillbirths, weak newborns, and growth retardation in piglets. Pathogens, such as porcine circovirus [

1], pseudorabies virus (PRV) [

2], and

Leptospira interrogans [

3], have been associated with reproductive failure in pigs.

These infections can be asymptomatic, causing only reproductive problems; some can be zoonotic. Leptospirosis, one of the most widespread bacterial diseases, shows variability in its pathogenicity [

3]. Similarly, infection with a PRV variant has now been demonstrated in people with neurological signs [

4].

The porcine lymphotropic herpesvirus (PLHV) is circulating widely in pig populations [

5]. Although the clinical implications in pigs have not been investigated thoroughly [

6], interest in this pathogen focuses on post-transplant lymphoproliferative diseases it can cause in pigs and humans [

5].

Currently, in Colombia, the prevalence and distribution of several pathogens and the health status of herds at the national level are unknown. Hence, it is necessary to generate control measures because of the increased costs of treatment and sanitary management [

2]. For this reason, this study examined the prevalence of porcine circovirus type 3 (PCV3), PLHV (1, 2, and 3), PRV, and

L. interrogans in the department of Tolima, using molecular techniques to expand the information available on the circulation of these pathogens in Colombia.

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tolima based on Law 84/1989 and Resolution 8430/1993 and complied with the guidelines for animal care and use in research and teaching [

7].

The samples were taken from breeding sows (n = 150) older than 250 days in five municipalities of the department of Tolima coming from farms with a record of reproductive problems, but there was no discrimination between sows with or without reproductive failure. The sample distribution was as follows: Ibagué (n = 15), Falan (n = 35), Chaparral (n = 15), Purificación (n = 35), and Cajamarca (n = 50). Whole blood was obtained by venipuncture of the jugular vein using the BD Vacutainer System (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA). gDNA was extracted from the blood samples using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification Kit (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

The DNA quality was verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of a fragment of the reference gene

gapdh (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). PCV3 was detected by amplifying the

cap gene, and

L. interrogans was detected by amplifying the

LipL32 gene. PRV, PLHV1, PLHV2, and PLHV3 were detected by amplifying the

glycoprotein B gene (

gB) using the specific primer for each pathogen (

Table 1). For

Leptospira detection, a positive control was used, which corresponds to the DNA from

L. interrogans Serovar

Icterohaemorrhagiae coming from a fresh culture extracted using a PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, USA). Positive control was gently donated by Professor Libardo Enrique Caraballo Blanco, Faculty of Education and Science, Department of Biology, Biomedical Research Group from the University of Sucre.

PCR was performed using a ProFlex PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) using Green GoTaq Flexi Buffer (Promega), according to the manufacturer's conditions. Amplicons were revealed on 2% agarose gel by electrophoresis (PowerPac HC; Bio-Rad, USA) using GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The gel was stained with HydraGreen (ACTGene, USA) and visualized with UV light using an ENDURO GDS gel documentation system (Labnet International Inc., USA).

The gDNA extracted from the blood samples showed quality values according to biomolecule spectrophotometry that were optimal for processing by PCR. In addition, all samples were considered good quality because the gapdh gene had been amplified correctly. The samples were used to detect the pathogens, where positive samples were detected for PCV3 and L. interrogans, regardless of whether these infected animals had reproductive failures.

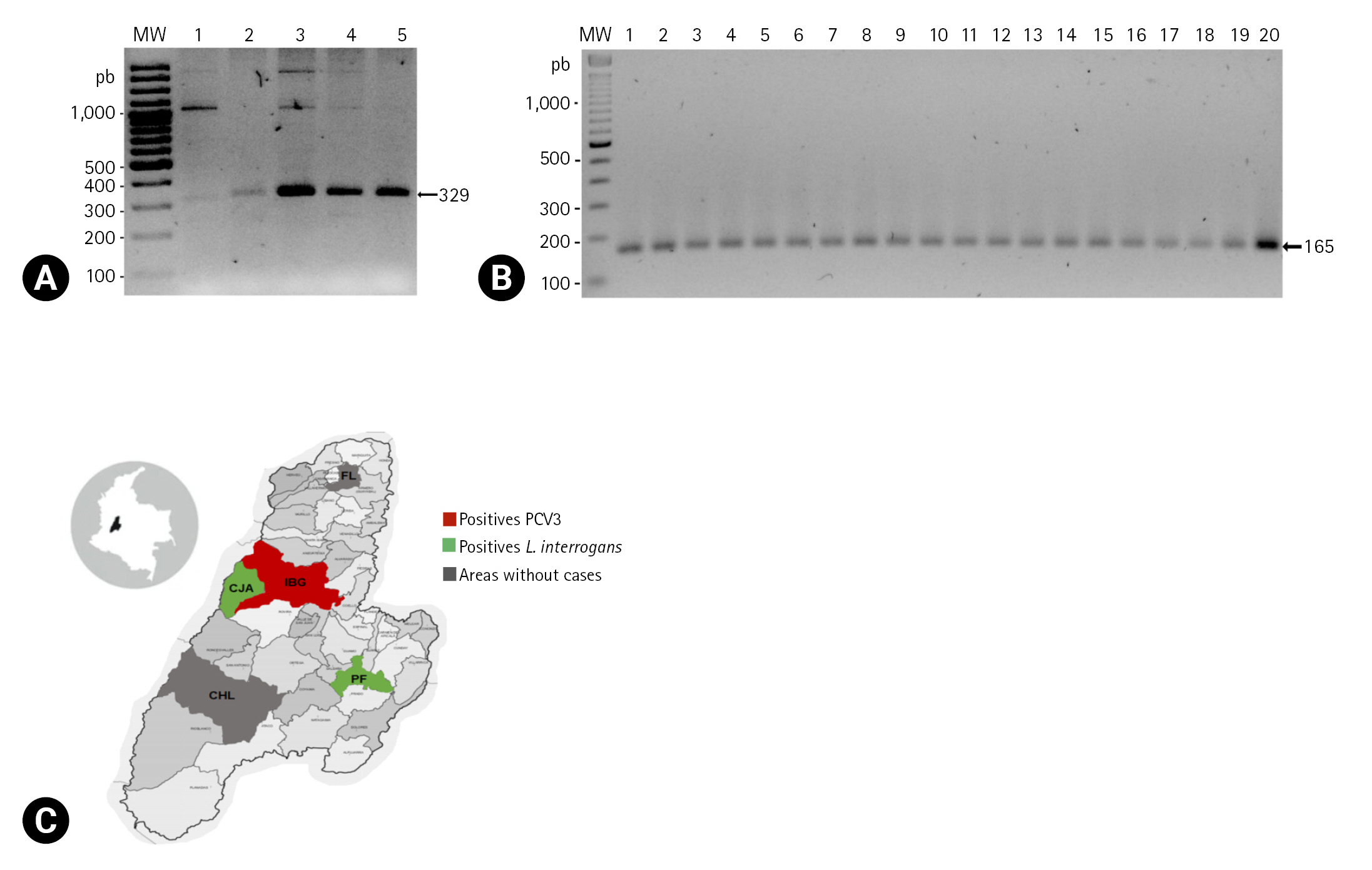

PCV3 was detected by amplifying a fragment of 329-base pairs (bp) of the

cap gene by endpoint PCR. Four samples (4/150, 2.7%) were positive, showing the band of the expected size on the electrophoresis assay (

Fig. 1A).

In the case of

L. interrogans, a 165-bp fragment of the gene that encodes for the LipL32 lipoprotein was amplified by endpoint PCR. Nineteen samples (19/150, 12.7%) were positive, showing the band of the expected size (

Fig. 1B).

Previously, the authors’ laboratory assessed the prevalence of PCV2 in these samples using molecular techniques [

8]; thus, coinfection with PCV3 and

L. interrogans was identified. Hence, 50% and 100% of the positive samples for PCV3 and

L. interrogans, respectively, were also positive for PCV2 (

Table 2) [

8].

In the present study, samples were taken from farm animals with a record of reproductive problems. PCV3- and

L. interrogans-positive individuals were detected by PCR. Some showed coinfection with PCV2 based on a previous study [

8]. Owing to this coinfection condition and the lack of complete information on the sanitary status of each animal, it was difficult to discriminate the causal origin of the reproductive problems in the farms, which can be multifactorial and even be associated with the interaction of the pathogens in the animal. Nevertheless, previous studies reported a lack of interaction between PCV3 and PCV2 [

9]. In addition, no vaccination for PCV3 is available in Colombia, which means PCV3-positive animals by vaccination is impossible. Moreover, the risk factors associated with PCV3 infections should be reviewed, including biosafety management in pig farms.

Several studies on PCV3 detection take serum samples because of the high PCV3 loads, which exceeded 10

3 (4.93 log genomic copies/mL) [

1], but previous studies showed that the serum might not be a suitable sample for PCVs detection mainly for the low viral load samples [

8,

10]. For this reason, whole blood was used to detect PCV3 in the present study. In the same way, whole blood samples are suitable for the molecular detection of

Leptospira spp. [

3] and PLHV [

6]. In the case of PRV, nervous tissues are more suitable for diagnosis because of the limited circulation of the virus in the blood, which may explain the negative results in the present study [

5,

11].

On the other hand, for a diagnosis of herpesviruses, serological methods are preferred because its detection in blood by PCR is not always possible [

2] owing to the periods of viral latency [

5]. This may be a cause of the negative results of this study, even though a higher number of copies of the PLHV genome in blood has been reported [

6].

Since the first report of PCV3, several countries in Europe, Asia, and America have detected the presence of the virus, despite a low prevalence in the animals tested. On the other hand, a prevalence of 97% has been reported in Brazil [

12]. In Colombia, a prevalence of 43.5% was demonstrated in groups of sera and 52.6% in tissues that showed genetic material of the virus [

13]. These results are considerably higher than those reported in the present study, where a prevalence of 2.6% was established in the department of Tolima.

Similarly, the presence of

Leptospira is reported in countries in America, Africa, and Europe. In the present study, a prevalence of 12.6% was shown in the department of Tolima, which is similar to those previously reported in Meta of 12.5%, compared to the reported seroprevalence of 89.2% [

14], which may indicate that pigs in the country are frequently exposed to the pathogen despite the low prevalence of infection. On the other hand, the specificity of the primers for the gene encoding for LipL32 allowed the detection of pathogenic

Leptospira, even though the infecting serotype was not identified. In Colombia, the circulation of the serovars Bratislava and Icterohaemorrhagiae has been reported in pig production [

14].

In South America, the only country that reports the prevalence of PLHV is Brazil, with 50% [

5], even though at the beginning of this decade, it was reported that it was distributed widely in the domestic pig population [

6]. In the present study, no sows showed the presence of DNA from these viruses in their blood, possibly because of the aforementioned problems with this type of tissue. On the other hand, PRV eradication has been reported in many Asian and European countries, as well as the United States [

2], except for China and Italy, where vaccination failures have been reported due to variants of the virus [

2,

4]. In Colombia, the Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario declared the country a zone free of PRV infections through serological surveys carried out from 2015 to 2019 [

15], which is consistent with the present results.

The coinfection rate of PCV3 with PCV2 was 50%, which is considerably higher than that previously reported in Colombia (6.4% in serum pools) [

13]. In Brazil, the coinfection rate is 26.4% [

12]. Similarly, coinfection between

Leptospira with PCV2, PCV3, and porcine parvovirus has been reported [

12]. PCV2 interacts with other pathogens generating an exacerbation of the disease [

9], but it is unknown whether this can occur between coinfection with PCV3 or

L. interrogans under the present conditions.

Sows of the department of Tolima revealed infections with PCV3 and L. interrogans, as well as coinfections with PCV2, in animals regardless of the clinical signs. It is necessary to establish the relationship of coinfection with reproductive failures in sows, and its associated risk factors and, based on molecular techniques, characterize the pathogens to establish surveillance and control measurements in this Colombian region. Similarly, the design of biosecurity strategies in pig farms will help reduce the risk of infection in animals and humans with pathogens with zoonotic potential.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print